by Dr. Karen Wieland and James Currie

And finally, we’ve arrived at the last of our 5 Word Meaning Change topics. And it’s such an amusing one, in a head scratching kind of way, we’re going to break it into two posts.

Almighty Janus!

As a winding, sideways introduction to the topic, let’s first introduce, or possibly reacquaint ourselves with, the Roman god Janus, pronounced like “PAIN-us”.

Janus was not one of the Olympian Big 12: in fact, he may be older than Jupiter, having been an original Italic god prior to the adoption of the Greek pantheon.

In any event, Janus was one busy guy. He was the god of gates and doorways and passages and hallways. Etymologically speaking, the Latin word for ‘door’ is the feminine form of his name: janua. Both are derived from the verb ‘eo, ire’, meaning ‘to go’.

Coming and Going

A key theme underpinning Janus’s busyness is the idea of transitions, moving from X to Y. He was also, and most remembered as, the god of beginnings and endings. The ending of X is a transition to the beginning of Y.

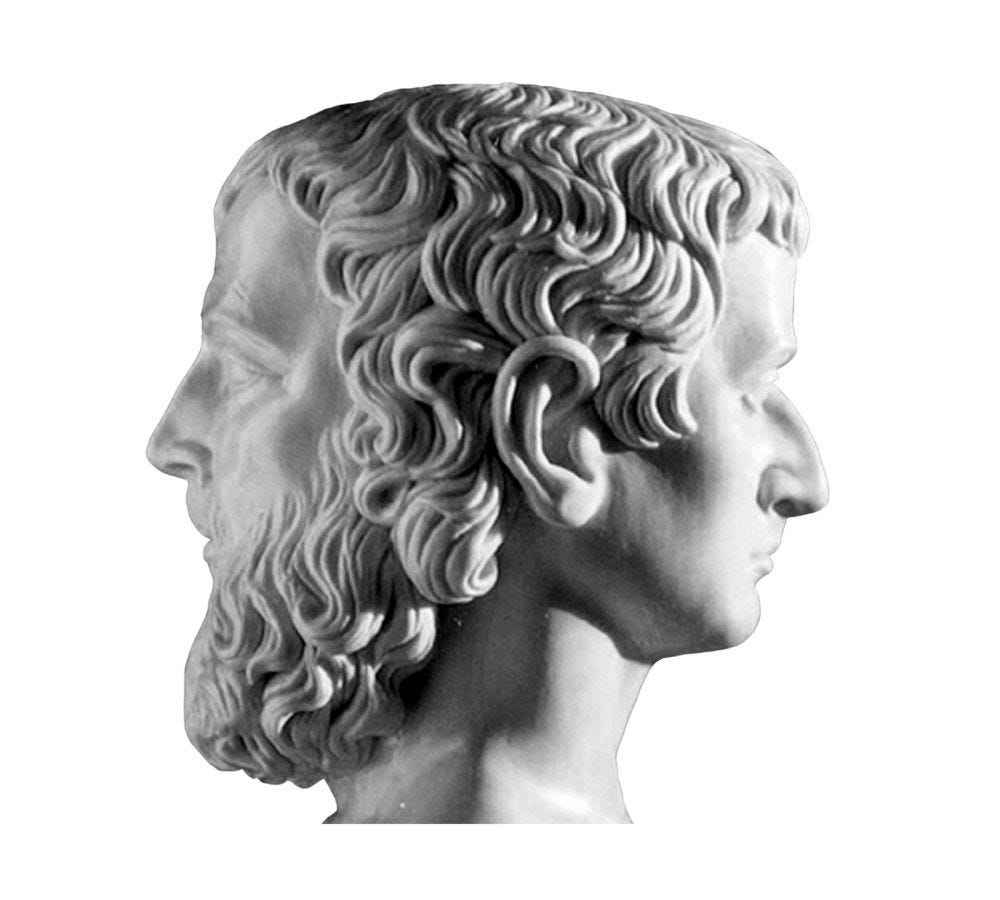

As you can see below, the idea of transitioning, leaving X for Y, is captured in traditional images of Janus: a male figure whose head has two faces, one – often older – looking back (at X), the other – often younger – looking forward (to Y).

And yet, Janus remains in our lives even today, though we may not have been aware of it. He marks the end of one year and the beginning of the new year at midnight on the first of…January, the month named after him.

Janus Words, a/k/a Contronyms

He’s also still around, but in admittedly a more obscure manner, in the idea of Janus words, words that are their own opposites. The linguistic term for a Janus word is a contronym. Contronyms have at least 2 meanings, and, most importantly, two of those meanings are opposite, either direct opposites or strongly contradictory.

Contronym itself means ‘opposite meaning’ (contra- (against) + -onym (meaning); the ‘o’ trumps the ‘a’, though both spellings – contronym/contranym – occur.

For Example…

A quick example: the verb ‘to sanction’ means on the one hand, ‘to approve something as being positive or favorable’. And yet, it also means ‘to penalize something for being negative, unfavorable or unapproved’. As in: “The committee refused to sanction the demonstration and sanctioned the organizers $500 each.”

How do Contronyms Form?

Contronyms develop over time in one of two different ways.

First, the modern English word originated from two different historical roots/words whose spelling and pronunciation converged over time.

However, it is much more common for a word to originally have had a small number of related meanings, one of which slowly shifted to the opposite, contradictory meaning.

Two Old Words Converged into One Modern Word

We’ll finish up this post with an example of a convergent contronym – there aren’t that many. In the next post, we’ll come back and talk about the second kind.

The “classic” example of a contronym that originated as two different words whose shape converged to the Modern English word is the verb ‘to cleave’, which can mean ‘to firmly stick something to something else’ AND ‘to remove something from something else, usually by cutting’. It is ironic: Addition ≠ Subtraction!

In Old English there were two verbs – ‘cleofan’ and ‘cleofian.’ I know, the ‘i’ doesn’t look like much but it makes a world of difference.

‘Cleofan’ – without the ‘i’ – meant ‘to divide, separate’ and comes from the Proto-Indo-European root *gleubh-, ‘to tear apart, cleave’. ‘Cleofan’ is a strong verb in Old English, meaning it forms its past tenses by changing the root vowel (as in “drink, drank, drunk”) and not by adding the ‘ed’ suffix (*”drinked”). That’s how we get the past tense forms ‘clove’ and ‘cloven’ for the modern verb.

‘Cleofian’ – with the ‘i’ – on the other hand, originated from the PIE root *gloi-, meaning ‘to stick’ (which also gives us the ModEng word ‘clay’). ‘Cleofian’ was a perfectly normal weak verb that formed its past tense with the OEng equivalent of ‘-ed’: cleofade, gecleofad. (See? That ‘i’ is important!). And thus we have the second set of past tenses ‘cleaved’ and ‘cleft’.

Through time, certainly by the Middle English period, the two verbs had converged to ‘cleven’, a single verb with both meanings. And I wonder why instead of ‘cleave’ and ‘cleave’ we usually say ‘stick’ and ‘split’.

Coming Soon: More Contronyms

Next time, those other contronyms!

Copyright © 2024 by aren M. Wieland, Ph.D and James E. Currie, Jr.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.